An Odd Couple Waxing Lyrical

by Alison Roberts

The Evening Standard

Without wishing to bestow the kiss of death upon one of the most promising bands in the country, I nevertheless must deliver some news to The Verve, viz: Andrew Lloyd-Webber is a big fan.

"I sit in my kitchen on a Sunday and listen to the Chart Show," he says. "I try and catch it wherever I am in the world … The Verve are very clever … there are some very, very well-made records around. All Saints are, you know, maybe a bit derivative, but it's well-made stuff. And I loved Jim's records with Celine Dion."

Jim Steinman is sitting next to Lord Lloyd-Webber in possibly the scruffiest pub in the seediest part of south London. Steinman, one of America's top song writers (the author of MOR hits such as Dion's It's All Coming Back To Me Now and the top-selling rock single of all time, Meat Loaf's I'd Do Anything For Love But I Won't Do That), wears an ice-cream cone whip of long grey hair and a fetching tie depicting a skull and crossbones. Lloyd- Webber is wearing brogues and casuals. Steinman somewhat unexpectedly drinks water; Lord Lloyd-Webber makes inroads into a pint of Guinness and I, stupidly, ask for a glass of white wine.

"I'm not sure that's wise," says Lloyd-Webber, one of the country's leading oenophiles. "You know. Pub wine …?" The landlord turns up the radio and - this happens only in the parallel universe known as Borough - Bitter Sweet Symphony suddenly fills the air.

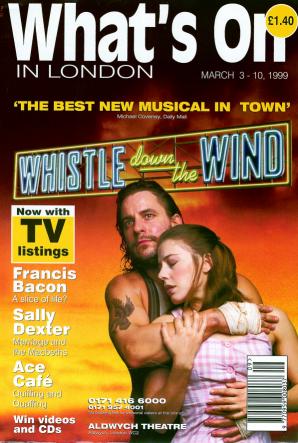

Jim Steinman has written the lyrics to Lloyd-Webber's new musical Whistle Down The Wind. He knew the 1961 British film version already because "there was a movie theatre near my house which showed foreign (sic) films and I was in love with Hayley Mills". Together, he and Lloyd-Webber have transferred this rather soppy story (bunch of Yorkshire kids discover escaped convict and, convinced he's Jesus Christ, shelter him from grown-ups) to 1959 Louisiana, where the heat, the music and the religion increase its potential.

"That period in America crystallises a lot of things," says Steinman.

"The children would get on, black and white, but at a certain age the cut-off happened and they were segregated," says Lloyd-Webber.

Steinman: "That period was about the birth of the teenager, of rock 'n' roll, of the freeway, and all this is perfectly right for the story which is essentially about a 14-year-old girl who's discovering sexuality, magic, God, music."

Lloyd-Webber: "And she lives in a family with no mother …"

Steinman: "Yep, we made much more of the fact that the mother had died …"

It's

quite hard keeping up with this self-confessed "odd couple". Steinman talks 10

to the dozen, and Lloyd-Webber nips in and out of the conversation with lightning speed.

They first met in the early Seventies, at the house of Australian entrepreneur Robert

Stigwood. "Either Tim Rice, or Andrew, was having a birthday party," says

Steinman, "and I was allowed to wander into the kitchen and watch them blow out the

candles."

It's

quite hard keeping up with this self-confessed "odd couple". Steinman talks 10

to the dozen, and Lloyd-Webber nips in and out of the conversation with lightning speed.

They first met in the early Seventies, at the house of Australian entrepreneur Robert

Stigwood. "Either Tim Rice, or Andrew, was having a birthday party," says

Steinman, "and I was allowed to wander into the kitchen and watch them blow out the

candles."

Ten years later, they lunched in Paris. "I was very intrigued by the mind behind Total Eclipse Of The Heart," says Lloyd-Webber. The pair discussed a possible collaboration on Phantom Of The Opera, then no more than an idea. But Steinman wasn't able to conclude the deal and made a Bonnie Tyler album instead. They remained in touch, however, and discovered they actually had rather a lot in common.

"I grew up wanting to do what Andrew did," says Steinman. "Theatre is what I love, but I ended up making records."

"Jim has got something of the Tim Rice about him," says Lloyd-Webber, "in that he loves his charts, and his rock 'n' roll. But the difference is Tim likes to play cricket and I can't see Jim or me on a cricket field. Much as I think Tim is an absolute genius lyricist, it's wonderful to work with somebody who is so big - the number one songwriter in America last year." That last accolade for Steinman comes from the Celine Dion single.

There is just one problem with Whistle Down The Wind: a try-out run in Washington two years ago, directed by "Mr Musical" Hal Prince, resulted in what can only be described as a flop. The critics were pretty savage and the show failed to set alight. Lloyd-Webber disputes this, though Steinman is quite frank about it.

"It played 99 per cent business, and we lost the one per cent because of the snow," says the former. "We made a $2 million profit, and it was fine. But I didn't want to carry on there … it wasn't right, or what I wanted. So I rang up a very, very old friend, John Eastman - Linda McCartney's brother - who's a hugely respected New York lawyer, and I said, 'I don't know what to do with this show. Jim and I really believe in it, but we're not sure it's going to be great if we move it to Broadway. Maybe we've got a director who just isn't a rock 'n' roller'. And he said, 'At your age and after what you've done, you can afford to be capricious. If you take it on to New York it'll come back to haunt you.' "

Steinman says the Washington production sucked, and that it didn't move him in the slightest. It was hurriedly and "carelessly cast", and "everyone involved was doing a lot of other things at the same time".

So Lloyd-Webber stopped the show, rang Jim and asked him if he had time to re-work the entire thing. Whistle Down The Wind was first premiered privately, at Lloyd-Webber's Sydmonton Festival some time before it hit Washington. It was to the Sydmonton version, and its cast, that they next turned. Gale Edwards replaced Hal Prince as director, and insisted that no one who worked in Washington be allowed to have anything to do with the London production. The show was radically changed.

"It's a whole new species," says Steinman.

"It's been hatched in a whole new season," says Lloyd-Webber, with satisfaction.

And with those confident assertions ringing in my ears, I nod to the landlord - whose white wine may or may not be up to scratch - and make my way back into the real world beyond the river.