The Selling Of Meat Loaf - What Makes Meat Loaf Cook?

By Michael Segell

Rolling Stone Magazine

The songs are myths, panoramas, vistas, voyages - voyages to a country of lost girls and golden boys who refuse to grow up. It's a land everybody wants to get to, a rock kingdom in which the major theme is: all revved up with no place to go.

- Jim Steinman, director/songwriter

"All I can say is: you can't take this shit seriously."

- Meat Loaf, actor/singer

The 400 or so record-industry types assembled beneath the canopied tent could have been heroic couriers in one of Jim Steinman's fantasy epics: earlier in the day they had mounted giant birds and flown thousand of miles to Cleveland, bearing glad tidings to the mythical rock & roll giant, Meat Loaf.

But they weren't. These were mere mortals who had helped sell a few million copies of Bat Out Of Hell, an album that is the collaborative vision of Marvin Lee Aday (Meat Loaf to you) and Jim Steinman. The executives, promoters, flacks, regional salesmen and assorted company minions assigned to the case by the CBS/Epic Records machine had come to bask in the glow of an unusual success story that was a still happening and that was being celebrated in a giant tent overlooking an outdoor amphitheater somewhere in the Cleveland-Akron-Canton vortex.

Earlier in the evening, Walter Yetnikoff, the natty lawyer who presides over CBS Records, had jetted in from New York lugging a platinum-plated copy of Bat Out Of Hell, a debut album that has defied all marketing odds and is now, a year after its release, beginning to probe the sales stratosphere. After awarding the coveted prize to the grunting, sweating Meat Loaf during his tour-ending Cleveland performance (his 170th date in less than eleven months), Yetnikoff danced a stockholder's jig before 19,000 devotees of Fat Rock while the band serenaded him and officials from Meat Loaf's label, Cleveland International Records, with a roily version of "River Deep, Mountain High."

But the news that Bat Out Of Hell had been inducted into the American Hall Of Platinum seemed almost lost in the buzz of statistics that resonated throughout the canopied tent after the show. Regional battles broke out between national and international account executives: Platinum in the States? Big deal, the album is Epic's largest Canadian seller ever. Oh yeah? What about Australia? Knocked Saturday Night Fever off its perch when the band toured down under this summer. Oh yeah? Sales outside the U.S. - a million and a half total. Oh yeah? The States are right in there: a million-four by early September, with 800,000 in the past three months. Oh yeah?

The corporate gloating continued into the early morning. Paeans were sung to the CBS research team that had determined that two out of every three Meat Loaf albums are sold to adult females, that Meat Loaf fans range in age from thirteen to thirty-five, that Kiss fans are Meat Loaf fans. Ingenious marketing and packaging skills were hailed, while everyone carefully avoided the word 'hype.'

The irony of it all is that, two years ago, CBS showed Meat Loaf and Steinman the door when the pair was looking for a label to back their unholy marriage of theater and rock. The arguments against the duo were formidable: the appropriately named Meat Loaf, who weighs something in excess of 250 pounds, was hardly the stuff of which groupies' dreams are made; much of the material - ranging from existential motorcycle ballads to graphic narratives of sex in a car- smacked of exploitation; eight-minute songs with two-minute instrumental overtures were not commercially viable; and the immense production schemes made Phil Spector's ideas sound austere.

"We had everything going against us," says Meat Loaf. "It took us three years, but we've vindicated ourselves."

Meat Loaf dumps his girth into a chair in his New York hotel suite and opens a can of diet soda. It is a few days after the Cleveland bash. Next to him, slumped in an over-stuffed chair, is Steinman, the brainy composer/pianist/choreographer who left the tour a month early to work up the songs for the next album (targeted for a spring release). For Steinman, whose schedule reverses night and day, the late-afternoon hour is less than godly. Looking something like a wizened teenager with his long gray-flecked hair, blue jeans and football jersey, Steinman stares out the window in foggy-eyed silence while Meat outlines the familiar tribulations suffered by musicians in search of a contract.

"We did thousands of voice and piano sessions," says Meat in his slightly oily Texas drawl. "We rehearsed at the Ansonia Hotel [in New York] for a year before we got sophisticated and brought people into a studio. People either loved or hated the music - most of them hated it."

Executives from RCA were apparently in the minority. They signed Meat and Steinman, only to have the pair walk out after the label refused to include Todd Rundgren's production skills in the package. (Rundgren had attended one of their rehearsals and agreed to produce and play guitar on the album.) "When we played the material and discussed the project with Todd, we knew we had to have him or nobody as producer," Meat says. "But RCA said, 'No Todd,' so we were back to singing duets at the Ansonia."

But production seed money was subsequently granted in spurts by Bearsville (Rundgren's label), by Rundgren himself and finally by Warner Bros., which agreed to release the album, but without promotion. Desperately, manager David Sonenberg played the tapes for Cleveland International, a fledgling production company composed of three former industry pros who agreed to swing their weight behind the project and hawk its potential to Epic Records.

"Very few people understood the scope of the project," says Steinman, shaking off his gray funk. "Even fewer seemed to be able to deal with the narrative."

To better understand Steinman's visionary wit, it helps to know that he lived in the same Amherst College fraternity house as David Eisenhower, whose ubiquitous bodyguards made the dorm the best-protected drug conduit in the Northeast. To understand Steinman's infatuation with teenage dreams, it helps to know that his apartment on New York's Upper West Side is decorated by a single snapshot of TV nymphet Kristy McNichol. To understand the dialect between the ordinary and the heroic that informs Steinman's songs, it helps to know that his favorite moment in all of rock & roll is Roger Daltery's stutter in the Who's "My Generation."

"My songs are anthems," Steinman says, "to those moments when you feel like you're on the head of a match that's burning. They're anthems to the essence of rock & roll, to a world that despises inaction and loves passion and rebellion, They're anthems to the kind of feeling you get listening to 'Be My Baby' by the Ronettes. That's what I love about anthems - the fury, the melody and the passion."

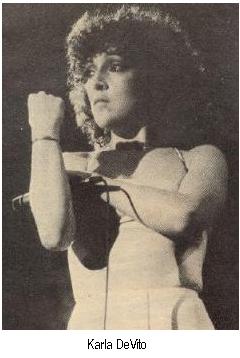

Delivering the passion is primarily Meat Loaf's job. Meat, who was granted his ignominious moniker in junior high school when he squashed his football coach's foot, has a soaring, screaming tenor that is equal to Steinman's and Rundgren's cathedral-like production of the album. And on-stage, Meat Loaf assumes even more heroic dimensions, conjuring up images of the Incredible Hulk, as during 'Paradise By The Dashboard Light,' he mauls his female counterpart, singer Karla DeVito. The image becomes frighteningly real when Meat acts out the show's "speeches" - vignettes written by Steinman to tie the songs together like a series of wildly irreverent dreams. One such speech directs Meat to bludgeon a varsity cheerleader and then his parents with a guitar that has a "heart of chrome and a voice like a horny fucking angel."

In Toronto, Meat got so carried away that he tumbled over the edge of the stage and tore ligaments in his leg, ending up in a wheelchair and off the road for a month. A legend has also been cultivated - and countered with accusations of hype - about his propensity for passing out after performances.

"The major thing that's happening there," Meat says, "is that I get so possessed by the songs, so wrapped up in the show, that it's like withdrawal when it's over. It's like I have to be exorcised from these Steinman demons. I get tired during the show, but I can't stop - and sometimes it gets fucking painful as hell." It sure looks it as Meat Loaf, his long, sweaty hair dripping onto his shoulders, stalks about the stage with the rage and fury of an Ajax, transforming a concert hall into the mise en scene of a mythic rock opera.

This blend of theater and rock & roll came naturally to Steinman and Meat Loaf when they hooked up in 1973. Meat, now thirty, had left his parents' comfortable home outside Dallas in 1966 and struck out for California, where he formed a band called Popcorn Blizzard (originally Meat Loaf Soul). The band stayed together for three years, opening for the Who, Iggy Pop, Johnny and Edgar Winter and Ted Nugent.

By 1969, Meat was living - sans band - in a communal home in Echo Park. He was looking for a job as a parking-lot attendant at the Aquarius Theater in Los Angeles when he met the lead in Hair, who suggested Meat audition for the show.

"It was like a cattle call," Meat recalls. "But I found out later that I looked like a guy named Joey Richardson, who had just left the show, so I got the part."

Hair brought Meat to Washington, Broadway and then Detroit, where he paired up with a soul singer named Stoney, who was in the production there. As Stoney and Meat Loaf they cut an album for Motown and toured with Rare Earth and Alice Cooper before Meat returned to theater in New York. In 1973 he appeared in Rainbow In New York and sang a gospel song from the show as an audition for More Than You Deserve, a play written by a Joseph Papp protege named Jim Steinman.

"The first thing I thought when I heard this voice," Steinman says, "was get this Negro music away from him. He should be singing Wagnerian rock opera."

Steinman's background is a similar crisscross of theatrical and musical paths. A New Yorker who spent his junior-high-school years in California, where his father relocated his steel distribution warehouse, Steinman studied classical piano for four years before leaping into rock & roll. He played in high-school bands, and then while studying drama at Amherst, formed a group called the Clitoris That Thought It Was A Puppy. In his senior year, Steinman's play, Dream Engine, caught the eye of producer Joseph Papp, who brought the young playwright/composer back to New York to work for the Shakespeare Festival.

Dream Engine was presented at the Newman Theater, the workshop that later launched A Chorus Line. By the time Meat auditioned for More Than You Deserve, Steinman had written and presented several plays and was considered a hot prospect in the New York theater world.

Over the next two years, Meat worked with Steinman and the Shakespeare Festival, sung one side of Ted Nugent's platinum album Free For All, and played the part of Eddie, the lobotomized Fifties degenerate, in The Rocky Horror Picture Show before hunkering down at the Ansonia to work up the material for Bat Out Of Hell.

Many of the songs had originally been written for a Steinman musical called Neverland, a futuristic version of Peter Pan that was presented at Washington's Kennedy Center last year and which Steinman is now talking to Universal Pictures about turning into a movie.

"It's about chemically mutated teenagers who can never grow up," Steinman says, "lost boys living in an antiseptic village who have never before seen a girl. Neverland is a place where being all revved up with no place to go is the excitement; the end product isn't important. Meat will play Tinker Bell, a barbaric, marauding mute, the image of pure physical power. Peter Pan is a fifteen year old John Travolta."

The second Meat Loaf album "will complete the vision of Neverland," Steinman says with a devilish sparkle in his eye that lends credence to what an astrologist once told him: that he has an overwhelming desire to astonish people.

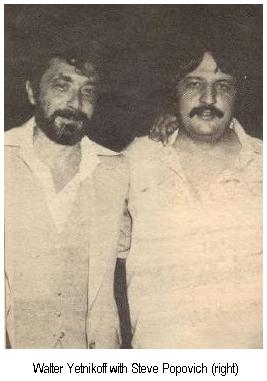

Despite the mutual backslapping at CBS' bacchanalian feast in Cleveland, the credit for Meat Loaf's success properly goes to Cleveland International Records. "Sometimes those parties can be a little self serving," said Steve Popovich, president of CI, as he recovered in his office from the previous night's orgy. "Hardly anybody makes it through the evening without being told how successful he is."

Popovich knows whereof he speaks. He and his two partners, Stan Snyder and Sam Lederman, are refugees from the CBS executive infrastructure who decided a year and a half ago to forsake six-figure salaries for the opportunity to work the corporation from the outside. Popovich moved to Cleveland and set up headquarters in his new house in Willoughby Hills. Snyder and Lederman remained in New York as liaisons to the corporate network. With over thirty years experience in the record business among them, they have a three-year contract whereby Epic retains their talent-scout services for what Popovich called "a modest figure."

"We weren't interested in wooing away major talent," said Popovich, the former head of A&R at Epic, as he stoked a bleary-eyed Snyder with coffee. "We just wanted the opportunity to work one album, not thirty at once."

"We decided on Meat Loaf because we were impressed with Steinman's songs and Meat Loaf's voice," explained Lederman. "We saw him at a live audition and it blew us away."

Record buyers in Cleveland and New York rallied immediately, but other markets were more difficult to penetrate. The plan was not unusual: get the band on the road, promote the hell out of the gigs and follow up performances by inundating local radio stations and record stores with picture discs, cassettes, acetates and posters. The only thing unusual about the campaign was its perseverance.

"Most new records get six weeks promotion if they're lucky," said Snyder, a former vice president of national accounts marketing at CBS. "We decided to push Bat Out Of Hell for a least a year, or for however long it took CBS to sink extra bucks into the project. But, hell, they were clamoring for the second album after Bat had sold 200,000 copies."

Meat Loaf, Steinman and the other seven members of the band peddled their operatic rock from city to city - and slowly the cities fell. Record sales in Toronto jumped from 2,000 to 26,000 in one week following a Meat Loaf performance. CBS saw fit to proffer more bucks. Shrewdly, CI had Meat Loaf play at the CBS convention last winter in New Orleans. CBS responded by commissioning promotional films of "Paradise," "Bat Out Of Hell," and "You Took The Words Right Out Of My Mouth" for use in England and Australia. London fell, then Melbourne. The CBS machinery then moved into high gear and saturated the media with advertising. By the night of the Cleveland performance, Bat was still racking up impressive weekly sales.

"It's not over yet," said the roly-poly Popovich. "The record will top out at over 5 million and "Two Out Of Three Ain't Bad" [the album's first hit single] is destined to become a standard sung in every Vegas nightclub by Jerry Vale and Steve Lawrence, and on the Tonight Show three times a week."

Aside from a few protests by isolated radio stations in the Bible Belt that "Paradise," the latest single, is too sexy for airplay, the album is getting maximum exposure in almost every major market except one: Los Angeles, city of 7 million. Three of the top album-oriented stations there have refused to play any Meat Loaf at all, claiming he's not for their audience.

Which makes Steinman pretty pissed off. Not because he stands to lose a few thousand bucks (he does) but because the whole objective of Bat Out Of Hell is to reestablish the distinction between rock & roll and passion and posing - and it is precisely the poseurs of so-called L.A. music that he wanted to obliterate. At the top of Steinman's list of frauds are Rod Stewart, Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles - the guardians of mid-Seventies rock.

So even though he has resolved not to slander L.A. radio while this jingoistic battle between the East and West Coast is being waged, Steinman decides to tell his L.A. story. Like the sagas in Bat Out Of Hell, it is not so much the retelling of an event as it is the description of a hallucination:

"I awoke about three a.m. on a floor littered with unconscious bodies in a hotel above Sunset Strip. It was at a time when the deal with Warner's was about to fall through. Earlier in the day, Meat had picked up these two identical twins - human surfboards with hair - and bought them back to the hotel. They cooked this huge duck in white wine sauce for dinner and when I woke up, the room was fairly dripping with it.

"I was looking out at the vista of violence that is L.A. - except out there they call it romantic violence - thinking about how I'd like to wipe away the stagnate dross of Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles with a single stroke. Then I saw this chemical fire in the distance. It was eerie - a blue and red haze everywhere. I felt like I was trapped in a jukebox. About ten minutes later all the smoke was absorbed into the valley and the network of city lights molted into electrical strings and veins. I thought: 'L.A. is a total junkie, the rouge on a scar. And Fleetwood Mac is the rouge.'

"Then Sam, the only other conscious person in the room, said he'd like to levitate. I said, 'Just stay where you are, because everybody else is sinking.' Suddenly the image dawned as a powerful metaphor for rock & roll: when everybody else is sinking and going the way of L.A. music, when fever and passion become an air-conditioned thrill and fantasies become cluttered by tax-returns, rock & roll dreams come through."